Introduction: The New Green Factory Dilemma

Some envision a future where fashion shifts from massive offshore factories to smaller, automated micro-factories closer to consumers. Instead of endless bulk production, brands could make garments on demand, cutting emissions, limiting overstock, and aligning with climate goals while still chasing profit. But this efficiency comes at a cost: for workers in places like Bangladesh or Vietnam, it raises a harder question—what happens when the jobs that sustained whole communities disappear?

For decades, garment factories in Bangladesh, Vietnam, El Salvador, and beyond have employed millions, fueling local economies and helping fund household expenses, including education. They have also provided wages for women and migrants who otherwise had few options, even if upward mobility remained limited. At the same time, these jobs have come with dangerous conditions and widespread exploitation, and the collapse of Rana Plaza remains a stark reminder of the human cost of fast fashion.

This paradox makes the issue deeply complicated. Factories can exploit, yet when production shifts or disappears, entire economies collapse, as Bangladesh has experienced during downturns in global demand. The textile and garment industry now faces one of its most disruptive transformations: a race to decarbonize, digitalize, and circularize. The question is no longer if change will come, but how it will unfold, and who will be left behind in the process. The fashion industry now faces a crossroads: can it pursue decarbonization and efficiency without hollowing out the very communities that made global supply chains possible? That is the true test of a just transition.

Fashion’s green transition may promise efficiency and lower emissions, but without centering workers and communities, it risks repeating old injustices under a new banner…solving environmental problems while hollowing out the very economies that built global supply chains.

From Safety to Sustainability

A decade ago, the collapse of Rana Plaza in Bangladesh, which killed more than 1,100 workers, forced the fashion industry to confront the stark reality of unsafe working conditions. In the years that followed, health and safety became the defining issue across supply chains. Today, the focus has shifted. Climate change, mounting waste, and the rise of ultra-fast fashion have pushed sustainability and circularity to the forefront.

The European Union is now attempting to set new global standards with eco-design rules and bans on destroying unsold stock. Major brands, including H&M, have responded with sweeping pledges. H&M, for instance, has committed to cutting emissions by 90 percent by 2040. Yet these shifts carry new risks. As Casper Edmonds of the International Labour Organization cautions, the drive toward greener and more digital operations could erode unionized, stable jobs and replace them with more precarious work, unless worker protections evolve just as quickly.

This shift demands more than cleaner factories or ambitious climate pledges; it requires building a future of work where sustainability includes people, not just products. The challenge is not only avoiding past mistakes, but also designing new systems that ensure workers thrive in the industries of tomorrow.

Beyond Jobs: Lives and Livelihoods

Conversations about a just transition too often narrow to reskilling, digital training, or factory upgrades, treating workers only as employees rather than whole people. As Fernanda Drumond of the H&M Foundation reminds us, a just transition cannot stop at the factory door. Workers are also parents, community members, and citizens, with needs that extend far beyond the paycheck.

True justice requires more than “future-ready jobs.” It requires inclusion, giving workers a real voice in shaping change. It requires agency, providing the power to act on those changes. And it requires accountability, building systems that hold brands and governments responsible for the outcomes of transition.

Workers’ lives are entwined with the health of their neighborhoods, their ecosystems, and their nations’ economies. A truly just transition must bridge the social and the environmental, ensuring that decarbonization uplifts communities rather than displacing them. Justice for people and justice for the planet are inseparable, and the fashion industry will be judged on whether it can deliver both.

Intertwined Justice: People and Planet

Too often, social protections and environmental goals are treated as parallel but separate tracks. In reality, they are inseparable. Wastewater from textile dyeing poisons rivers, eroding both ecosystems and the health of nearby communities. Mountains of discarded clothing pile up in landfills behind people’s homes, compromising human dignity as much as environmental safety.

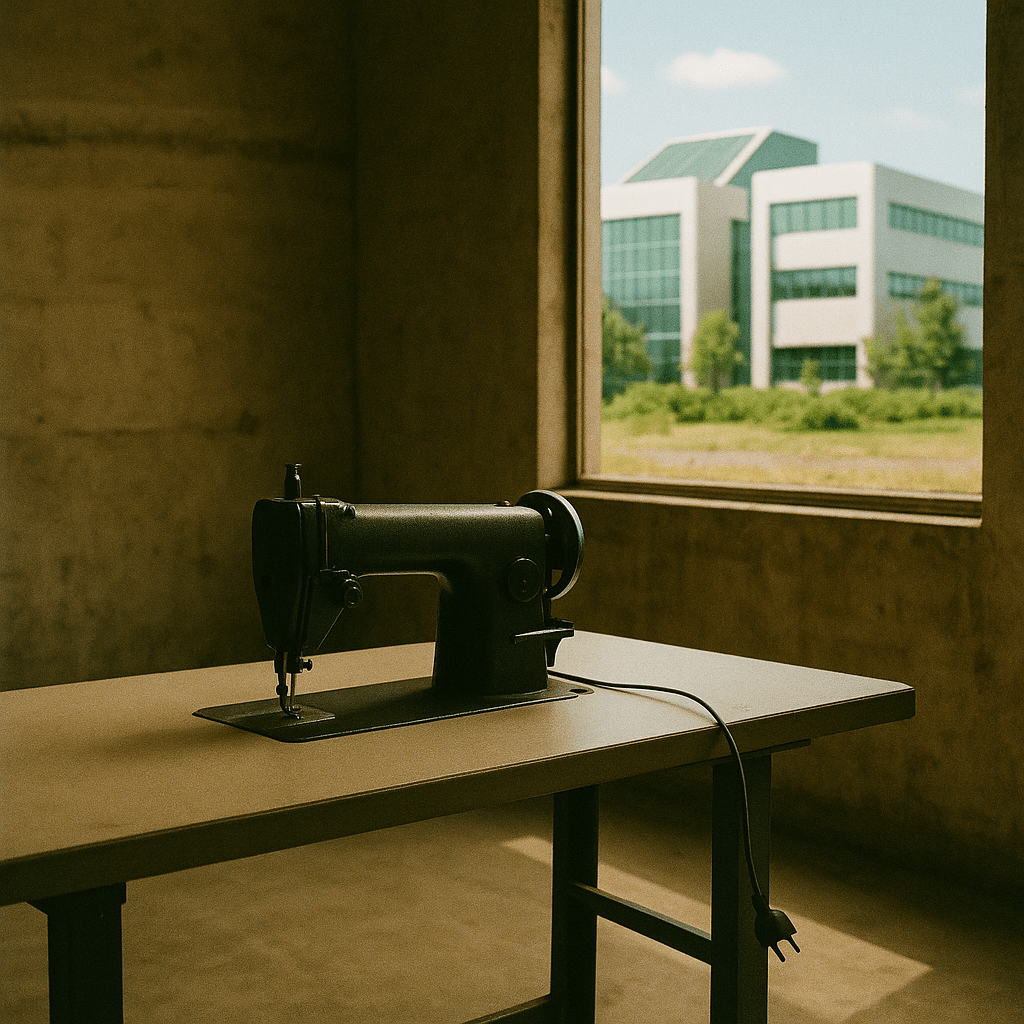

Justice in fashion cannot be one-dimensional. Regenerating ecosystems and sustaining livelihoods must be seen as part of the same project. Without that, “green factories” risk being little more than greenwashing. As Salvadoran union leader Marta Zaldaña put it: “Green factories do not always equate to green jobs.”

Regional Realities

Transition is Not One-Size-Fits-All

- In Bangladesh, garment exports power the economy, but workers—mostly women—are vulnerable and awareness of circularity remains limited.

- In the MENA region, water scarcity complicates the push toward greener factories.

- In Latin America and the Caribbean, labor rights remain fragile even as “green” production expands.

- In Nigeria, an influx of second-hand clothing undermines domestic industries.

These diverse realities highlight a central truth: the path to a just transition cannot be uniform. It must be tailored to local contexts, with equity at its core.

What Real Transition Demands

A truly just transition is multifaceted. It demands future-ready skills, but also living wages and universal protections. It requires unions not just to survive but to expand into new sectors like repair, recycling, and digital logistics. And it must treat planetary regeneration as an industrial priority, not a peripheral goal.

The H&M Foundation’s Oporajita initiative in Bangladesh offers a glimpse of what this could look like in practice, equipping women garment workers with digital skills while embedding inclusion and environmental well-being into its design. But for such models to scale, systemic investment, co-creation, and accountability are essential.

Embedding Justice at the Core

The textile industry has a once-in-a-generation opportunity to rebuild itself around sustainability and equity. But efficiency alone will not be enough. If transitions prioritize carbon savings while sidelining people, the result will be communities hollowed out in the name of progress.

The vision for 2050 is ambitious: a net-zero, circular industry where ecosystems thrive and livelihoods are secure. But ambition alone won’t deliver it. Fashion must move beyond treating justice as an optional add-on. It must design it into every decision, making fairness the default rather than the dream.

Because in the end, circularity that ignores justice falls short of true sustainability. And the future of fashion will not be measured only in emissions reduced, but in communities sustained.